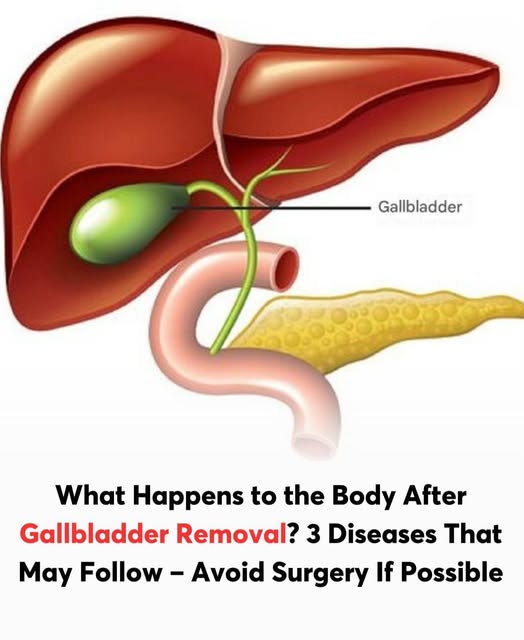

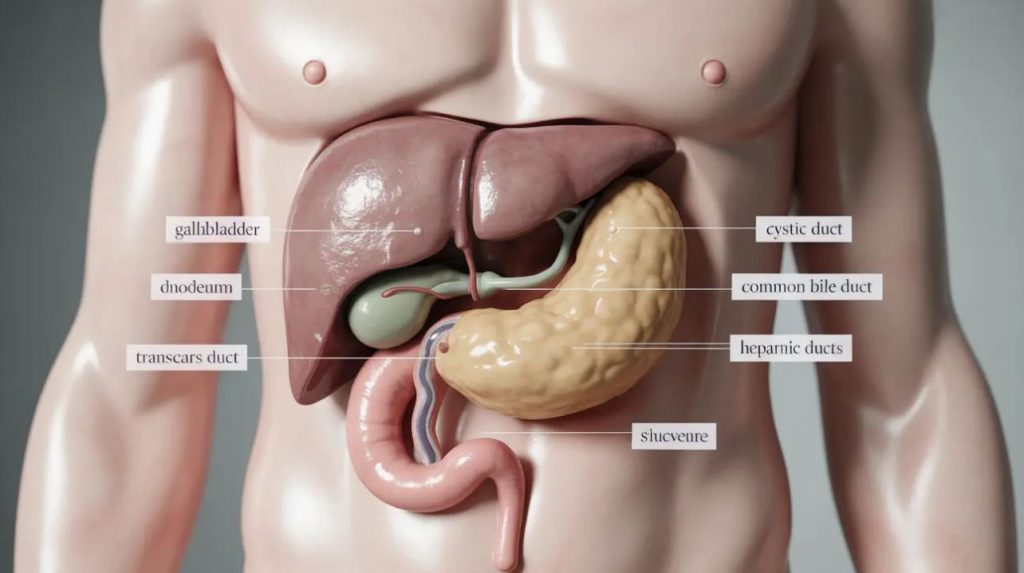

The gallbladder sits just beneath the liver and plays a role in storing and releasing bile, which helps your body digest fats. Many conditions can prompt its removal, including gallstones, inflammation, pancreatitis linked to gallstones, and, in very rare cases, cancer. While people typically live a normal life without a gallbladder, the surgery can trigger some side effects. Below is an overview of what to expect post-surgery and some helpful dietary guidelines.

Physical Adjustments After Surgery

Most gallbladder procedures involve a cholecystectomy, in which the organ is removed. Because the gallbladder is not essential, many patients return to regular life. However, adjustments happen. In the weeks following surgery, bile drains continuously into the intestinal tract, rather than being released in controlled bursts. This change can irritate the bowel and contribute to diarrhea, which is reported by up to 20 percent of people after surgery.

You may also experience bloating, gas, and indigestion, especially early on. Fat digestion is less efficient without a gallbladder, so your body may struggle temporarily to manage heavier meals.

A small fraction of individuals develop post-cholecystectomy syndrome, a cluster of symptoms such as upper abdominal discomfort, nausea, and digestive upset. In rare circumstances, gallstones may still form in the bile ducts (a condition known as choledocholithiasis), leading to pain and possible infection.

In some cases, the intestine’s ability to reabsorb bile is overwhelmed, resulting in bile acid malabsorption. That can cause persistent loose stools and reduced absorption of fats in a minority of patients (around 5 to 10 percent).

Appetite, Weight and Eating Patterns

After surgery, many people find that greasy, rich foods become intolerable. Some experience sudden weight loss simply due to reduced appetite or fear of triggering symptoms. Others may gain weight if they shift toward processed, easy-to-eat foods.

In the first few days, a clear-liquid diet—such as broths, gelatin, and diluted fluids—is often recommended. Alcohol should be avoided initially. Gradually, you can reintroduce small, solid meals as tolerated. Over time, most patients transition into a more normal diet by around four to six weeks post-op.

Recommended Foods and Nutrients

Selecting low-fat, easily digestible foods helps minimize GI distress. You’ll want to stay well-hydrated, especially if diarrhea occurs, by drinking water, electrolyte solutions, or light broths.

Good options include whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and fat-free or low-fat dairy alternatives. Soluble fiber is especially helpful—sources like oats, carrots, beans, and spinach may slow digestion and reduce irritation.

As you progress, gradually increase fiber intake, introducing foods such as prunes, oat bran, chickpeas, beets, and okra. Keeping a food journal can help you identify specific triggers or troublesome items.

Foods to Avoid or Limit

In order to prevent common side effects like diarrhea and cramping, avoid fatty and fried foods like bacon, lard, heavy cream, butter, and processed meats. Spicy foods, especially those with capsaicin or strong seasonings, may aggravate digestion.

Be cautious with sweets, high-fat dairy products, and caffeine—all of which have the potential to worsen gastrointestinal symptoms. Processed baked goods and sugary snacks should be minimized, especially early in recovery.

Transitioning to Normalcy

Most individuals are able to resume a relatively normal diet after about a month. However, it’s wise to proceed slowly and pay attention to how your body responds. If certain foods repeatedly trigger discomfort, it may be best to limit or avoid them indefinitely. Over time, many find a balanced, moderate diet works well.

Tips for a Smoother Recovery

Eat smaller meals more frequently rather than a few large ones.

- Chew thoroughly and eat slowly to reduce digestive burden.

- Track your foods and symptoms to spot patterns.

- Introduce new foods gradually, rather than all at once.

- Maintain hydration, particularly during bouts of diarrhea.

- If discomfort resists dietary adjustments, consult a healthcare professional or nutrition specialist.

Conclusion

Living without a gallbladder is completely manageable once your body adapts to the new way of digesting fats. The first few weeks may bring mild discomforts such as bloating or diarrhea, but these typically ease with time and mindful eating. Focusing on smaller, balanced meals and avoiding greasy or overly rich foods helps the digestive system adjust more smoothly. Long-term, most people experience little to no disruption in their overall health or energy levels. By emphasizing hydration, fiber-rich foods, and lean sources of protein, you can support both digestion and nutrient absorption. Paying attention to your body’s signals and making gradual dietary changes are key to preventing post-surgery complications.