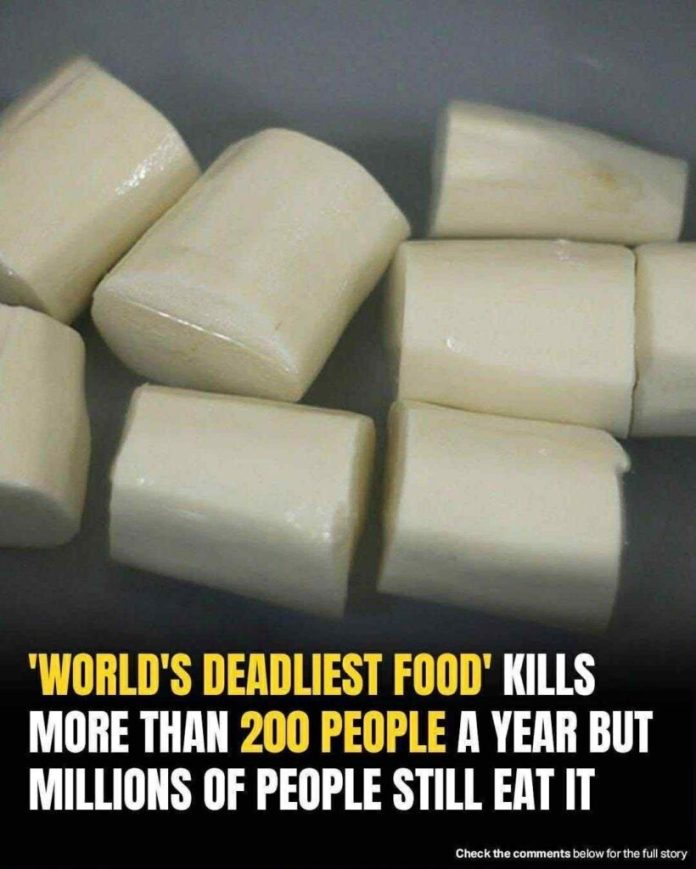

One of the most dangerous foods in the world is not an exotic delicacy — it’s a humble root vegetable consumed daily by hundreds of millions of people worldwide. This food is cassava (also known as yuca or manioc). Despite its wide popularity and vital role in sustaining communities, cassava has a hidden menace: when improperly prepared, it can release compounds that are lethal.

Cassava is notably a survival crop. It thrives in poor soils and dry climates where many other staple crops fail, making it essential for food security in large parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Its versatility is also impressive: it can be boiled, mashed, dried into flour, turned into porridge or chips, used in baking, or processed into tapioca.

The Hidden Danger: Toxic Chemicals Inside

What makes cassava dangerous are natural chemicals it produces — cyanogenic glucosides. These compounds are part of the plant’s defense mechanism against pests. When the root is bitten, crushed, or left unprocessed, these compounds can convert into hydrogen cyanide, a potent poison that attacks the human body. If cassava is eaten raw or inadequately processed, this cyanide release can cause serious harm. Symptoms of poisoning include dizziness, nausea, rapid breathing, and in severe cases — paralysis or death. The danger is highest when people rely heavily on cassava without access to safe processing methods. Indeed, improper preparation of cassava leads to over 200 deaths globally each year. Many more suffer from long-term health effects or chronic poisoning. This grim reality has earned cassava the reputation of being among the “deadliest” foods in the world — yet despite this, it remains a dietary staple for roughly half a billion people worldwide.

Why Cassava Remains Essential

Given the risks, one might wonder why cassava is still widely eaten. The answer lies in practicality and necessity. In many tropical and subtropical regions, cassava is often the most reliable crop available. It flourishes even when weather conditions are harsh, soils are poor, and other crops fail. Nutritionally, cassava provides a dense source of carbohydrates — crucial calories for populations where food scarcity is a persistent issue. It keeps people fed when alternatives are limited or unaffordable. Also, cassava’s culinary versatility makes it a valuable gastronomic ingredient. It can be transformed into flour, chips, porridges, traditional breads, and more. In many communities, it has become a cultural staple.

How to Make Cassava Safe

Although cassava can be deadly raw, there are ways to make it safe. Traditional processing methods significantly reduce the cyanide risk. These include peeling, thorough soaking, fermenting or drying, and cooking thoroughly. These steps help neutralize toxic compounds before consumption. When properly prepared, cassava becomes a nutritious, safe food — providing energy, vitamins, and minerals without the poisoning risk. For many communities, mastery of these preparation steps is not optional: it’s essential for survival.

A Reality of Risk and Necessity

The story of cassava highlights the complex balance between dietary necessity and danger. For hundreds of millions of people, cassava is not a gourmet choice — it’s a vital food that sustains families, especially where other crops cannot grow. But this necessity comes with responsibility: improper preparation can lead to tragedy. Ultimately, cassava remains both a lifesaver and a silent threat. With awareness and correct processing, communities can continue to rely on it for nutrition and survival — but without care, its consumption can be deadly.