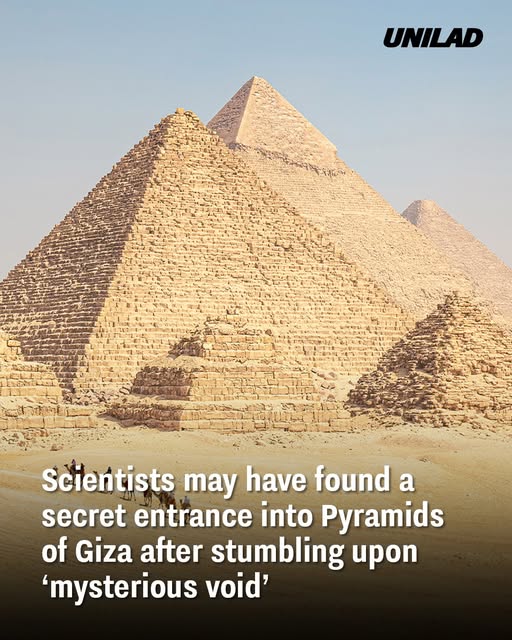

Researchers scanning the Pyramid of Menkaure the smallest of the three major pyramids at Giza have detected unusual internal spaces that could hint at a previously unknown entrance or passageway inside the ancient structure.

The findings come from an international research effort by scientists from Cairo University and the Technical University of Munich under the ScanPyramids Project, which uses advanced scanning technologies to study the internal layout of ancient monuments without physically disturbing them.

How the Discovery Happened

The team focused on a section of the pyramid’s eastern side where unusually smooth granite blocks had long puzzled archaeologists — similar to the finish around the known northern entrance. Using a combination of ground-penetrating radar (GPR), ultrasound scanning, and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), researchers identified two separate air-filled voids hidden just behind this polished outer façade. These voids are not visible from the outside and were detected solely through the non-invasive imaging techniques. The voids sit approximately 1.13 to 1.4 meters (about 3.7 to 4.6 feet) beneath the exterior surface and each measures roughly 1 meter by 1.5 meters (about 3.3 feet by 4.9 feet) in size.

Could It Be a Hidden Entrance?

The presence of these air-filled gaps has reignited a long-standing archaeological theory: that the Menkaure Pyramid may contain a secondary entrance or passage that has remained undetected for millennia. While the voids themselves do not yet constitute an actual corridor or confirmed doorway, their location — directly behind a section of polished stone similar to known entryways — suggests they could be related to a sealed or structural space created during the pyramid’s construction. Archaeologists have discussed this possibility since at least 2019, when the smooth granite face was first proposed as a candidate for an alternate entrance. Modern imaging now gives the most detailed view yet of what lies behind it.

The Pyramid’s Long History

Built more than 4,500 years ago, the Pyramid of Menkaure is believed to house the tomb of King Menkaure, a ruler of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty. Unlike its larger neighbors — the pyramids of Khufu and Khafre — Menkaure’s tomb has long remained less studied and more enigmatic. This new discovery marks one of the most intriguing advances in the study of this structure in decades and follows other breakthroughs made with similar non-destructive methods at the larger pyramids on the Giza Plateau.

What It Means for Archaeology

Experts emphasize that while the voids are significant and well-verified through multiple technologies, further investigation is needed before they can be definitively interpreted as an entrance, corridor, or any particular type of archaeological chamber. Still, the discovery demonstrates the growing power of non-invasive scanning techniques in uncovering hidden structures within ancient monuments, potentially opening new frontiers in our understanding of ancient Egyptian tomb architecture.

Moving Forward

Researchers plan to continue analyzing the data and exploring whether future scans or technologies might reveal even more about the mysterious voids. Any confirmation of a hidden entrance could reshape historians’ understanding of how pyramids were built and used — highlighting yet another secret waiting to be unlocked beneath the sands of Egypt.

Conclusion

The discovery of mysterious voids inside the Pyramid of Menkaure adds a compelling new chapter to the ongoing study of ancient Egyptian engineering. While researchers have not yet confirmed the exact purpose of these hidden spaces, their location and structure suggest they could be linked to a sealed entrance, passageway, or an intentional architectural feature lost to time. What makes this finding especially important is the use of non-invasive technology, which allows scientists to explore one of the world’s most iconic monuments without causing damage. As further analysis continues, these voids may help historians better understand how the pyramids were constructed and used, proving that even after more than 4,500 years, Egypt’s ancient wonders still hold secrets waiting to be uncovered.