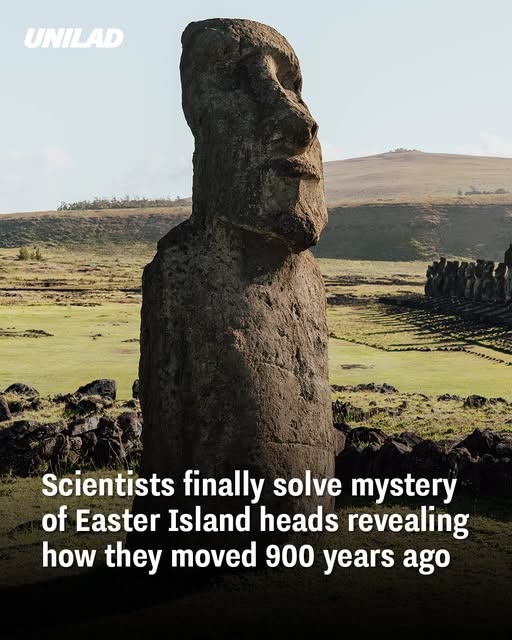

For centuries, the question has haunted historians, archaeologists, and curious onlookers alike: How did the people of Easter Island move the colossal moai statues across difficult terrain? These monolithic figures, each weighing many tons, stood as imposing silent witnesses to the ingenuity of the island’s former inhabitants. Many theories have been proposed — rollers, sleds, brute force — but none fully satisfied.

Now, based on recent experiments and modeling, researchers believe they have finally cracked the puzzle. The answer lies not in brute strength or mechanical contraptions, but in a clever, coordinated motion that makes the statues appear to “walk.”

A Walking Motion Is Proposed

The new hypothesis holds that the moai were transported upright using ropes and a side-to-side rocking motion. In this technique, teams pulled simultaneously from opposite sides, tipping the statue gently from left to right, then forward, repeating this in a controlled zig-zag cadence. The statues’ bases are slightly curved and their design allows just enough flex to enable this rocking progress. A test using a 4.35-ton replica provided proof of concept: with a group of around eighteen people, the statue was moved over a distance of 100 meters in about 40 minutes. This supports the notion that large monoliths could be “walked” into place with relatively modest manpower, if the motion is well controlled and the terrain suitable. One observed advantage is energy efficiency. Once the statue begins to move, it requires less effort to keep it going. The main challenge lies in initiating the rocking motion in the first place, but once in motion, the technique proves remarkably stable and manageable.

Ancient Roads and Statue Design

The researchers also note that the island’s roads appear to have been constructed specifically to facilitate this walking method. Some segments overlap or run parallel, suggestive of incremental clearing and construction in precise sequences. The paths are just wide enough for the statues to traverse while rocking side to side. Furthermore, the D-shaped bases and slight forward lean in many moai designs align perfectly with the requirements of rocking motion. These structural features would help the statues tip gently and return to equilibrium during movement. By combining field experiments, computer modeling, and archaeological evidence, the research team argues that this walking method is the only one consistent with what is physically plausible and consistent with the evidence preserved on the island.

Implications for Rapa Nui Ingenuity

This new model provides not only a mechanical explanation but also a deeper insight into the engineering sophistication and resourcefulness of the Rapa Nui people. It emphasizes that they likely understood leverage, balance, and coordinated effort — and deployed those principles at scale. Some past theories, such as using rollers or sleds, required vast numbers of people or wood resources that may not have been available. Others ventured into speculative territory, evoking supernatural or alien interference. The walking hypothesis, however, roots the solution firmly in observable principles—one that can be tested, reproduced, and adjusted based on evidence. The study’s authors challenge critics to propose evidence that could conclusively disprove this method, noting that so far, no such alternative has held up under scrutiny.

A New Chapter in Ancient Engineering

If accepted broadly, this breakthrough resolves one of archaeology’s longest-standing riddles. It reframes the moai not as static wonders but as marvels that once traversed the landscape by human guidance and clever technique. The idea that these statues “walked” into position invites us to rethink not just Easter Island’s past, but the capacity for innovation in isolated societies. Beyond solving a puzzle, the discovery honors the legacy of the island’s builders — not as mystical figures but as skilled engineers, capable of transforming their designs into motion. The monumental statues were not hauled; they walked.