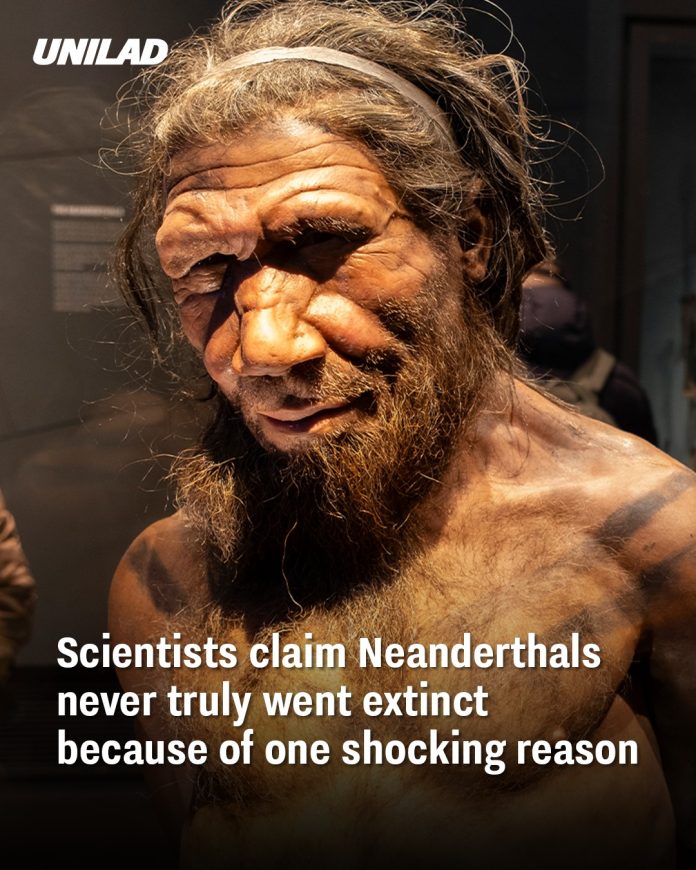

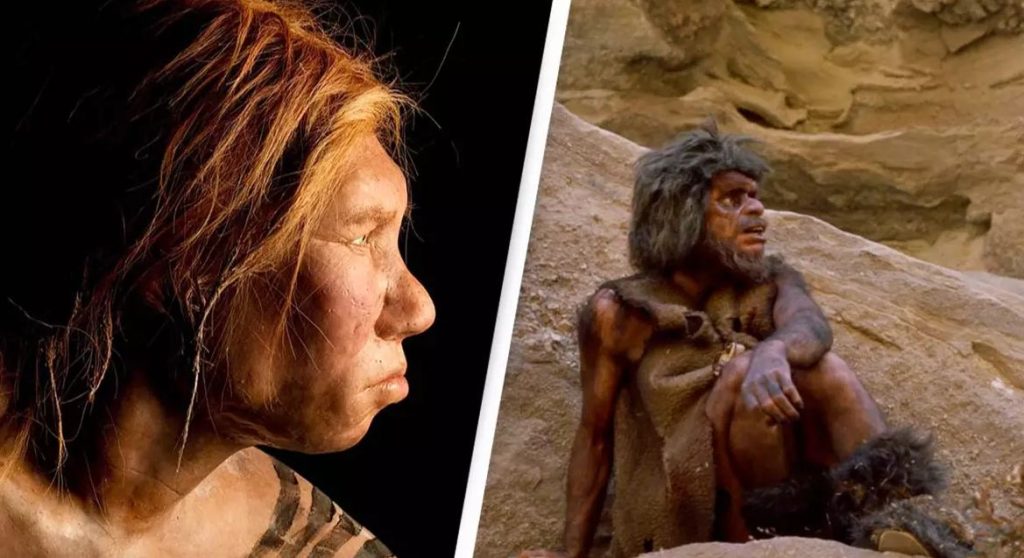

New scientific findings suggest that Neanderthals did not disappear in a dramatic extinction event, but rather were gradually assimilated into modern human populations. Rather than vanishing forever, their genetic legacy survived by blending into the DNA of early Homo sapiens. This perspective challenges the traditional image of Neanderthals as a completely separate lineage that was wiped out.

How Interbreeding Changed the Narrative

Genetic studies reveal that ancient Neanderthals and early modern humans interbred multiple times across tens of thousands of years. These interactions were not rare or isolated: rather, there were sustained periods when the two groups exchanged genetic material. Over time, this mixing caused their distinct lineage to fade, as human populations grew and spread.

The Assimilation Model Explained

According to the assimilation model, successive waves of migrating humans gradually integrated Neanderthal groups. In small, fragmented Neanderthal communities, inbreeding was common, which limited their genetic diversity and reduced their population resilience. Meanwhile, large, interconnected human populations maintained greater diversity and stability, enabling them to absorb Neanderthal genes more effectively. Eventually, Neanderthals ceased to exist as a separate population and became part of the broader human family.

A Genetic Legacy in Every One of Us

Modern non‑African human populations typically carry between 1 and 4 percent of Neanderthal DNA. These traces are not random leftovers — they influence many aspects of biology, from immune response to how certain traits develop. In some lineages, Neanderthal genes provided beneficial adaptations for early humans living outside of Africa: parts of their DNA gave advantages in skin and hair proteins, as well as environmental resilience.

Why the Y Chromosome Disappeared

Interestingly, analysis of modern genomes shows that almost no Neanderthal Y chromosome (the male-specific chromosome) survives today. Scientists propose that this may have resulted from hybrid offspring fertility issues, or from chromosomal mismatches over generations. Because male hybrids may have had reduced reproductive fitness, Neanderthal Y lineages likely declined faster than other types of Neanderthal DNA.

Small Populations, Big Consequences

Neanderthals probably existed in relatively small, isolated communities, which made them vulnerable. Research into their genetic remains shows signs of inbreeding and low genetic diversity. These conditions would have limited their ability to maintain a large, stable population — especially when faced with expanding human groups. Their isolation may have prevented them from forming broader networks to survive as their numbers declined.

Blended, Not Lost

Rather than disappearing entirely, Neanderthals seem to have been absorbed into Homo sapiens through repeated interbreeding. Over long time periods, their genomes merged with ours. The merging was subtle, but powerful: genetic signatures from Neanderthals still echo through the DNA of people living today. Their presence within us is not a survival of their species as a separate group, but as a shared heritage.

Why This Changes How We Think About Extinction

This view transforms the story of Neanderthals: they are not just a “species that died out,” but ancestral relatives who became part of a larger human population. It also highlights how populations evolve — sometimes not through sudden disappearances, but through blending and gradual integration. Humanity’s history, in this sense, is not just about survival of the fittest, but about complex relationships and shared lineage.

What This Means for Future Research

Understanding the Neanderthal legacy is more than a scientific curiosity: it changes how researchers study human evolution. Scientists continue to analyze ancient genomes to map precisely which Neanderthal genes remain, and how they impact modern biology. As more data emerges, humanity’s story becomes richer, revealing not only how we diverged from our ancient cousins, but also how we came back together.